Ray Casting in 2D Grids

Ray casting is used in many different areas of game development, most commonly for visibility, AI (often for visibility though) and collision detection and resolution. If you are making a game, chances are you need ray casting somewhere. I started this blog post over a year ago, but decided to not write it up fully and publish it, since I thought that it might be a little embarassing, since most if it is too trivial. But I still find it fairly hard to find any good information or example code on this and on the weekend of Global Game Jam 2016, I forgot how to do it properly and didn’t find any good resources on this, ending up debugging ray casting code for a little over 3 hours (unnecessarily, I think). So if this actually helps no one then this shall remain as a memorial of shame for myself. Or as a handy reminder, so history does not repeat itself in a way that leaves me debugging ray casting code for hours.

The relevancy of grids is given by the prevalence of tile based games and even if the game is not tile based, because of optimization structures for collision detection/physics or other gameplay elements that are often in place, being either directly (simple uniform grids) or indirectly (e.g. quadtrees) related to grids.

Throughout this article, our grid will be a uniform grid with cell size grid.cellSize.

The ray will be a tuple of a point (it’s origin) and a vector (it’s direction), namely ray.startX, ray.startY and ray.dirX, ray.dirY. The set of points on the ray is then described by: {ray.start + t*ray.dir | t is a real number} and we can “address” every point on the ray with a value t.

All methods presented here on out are implemented in this GitHub repository (rather badly most of the time, since I started this project over a year ago so this is a little patchwork-ey, but I put some work into refactoring, so it should be bearable):

https://github.com/pfirsich/ray-casting-test

The Naive Method

The simplest, but often times an adequate way to do it, is stepping uniformly in world coordinates. In our case, where our ray direction is not normalized, we can not just step uniformly in t, but must use our normalized direction vector multiplied by the step size (again: in world coordinates).

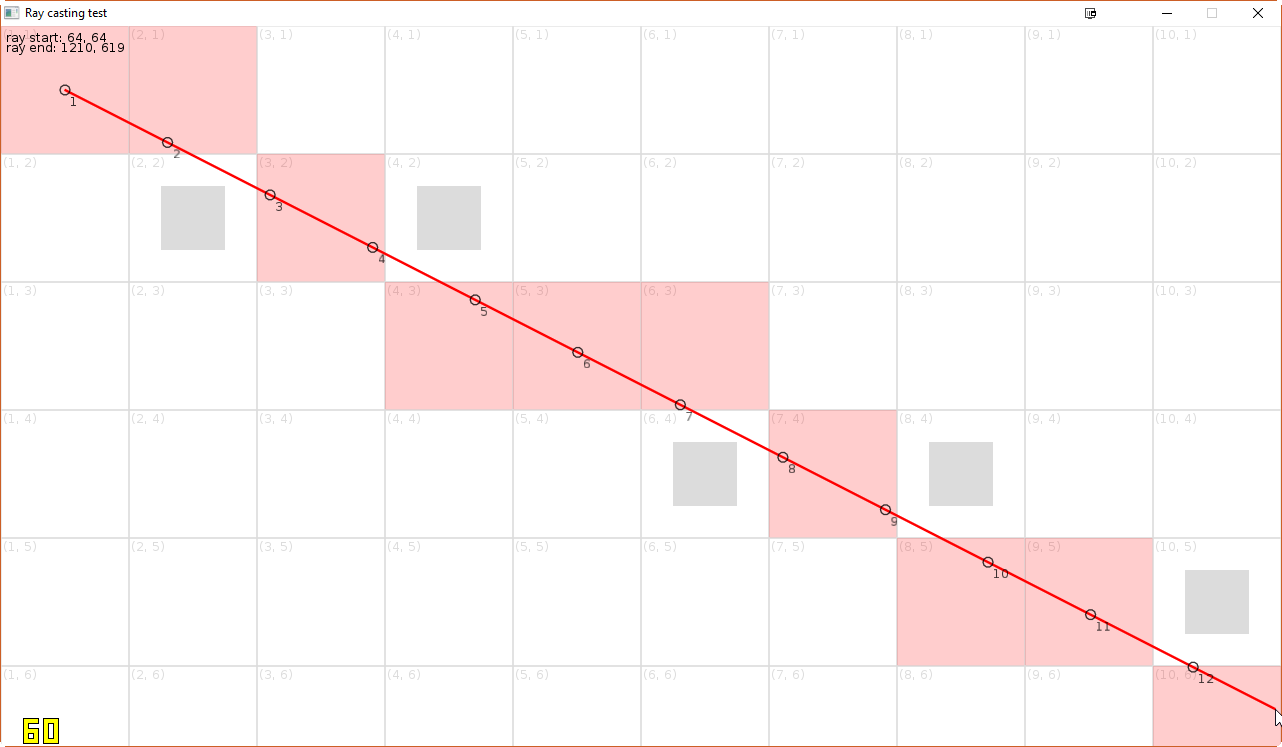

Even if often times this is sufficient, it is never perfect in the sense that this method finds all cells that intersect with the ray and with finite dt, there will always be corners that could be overstepped. An example of this from the example löve program (function castRay_naive) can be seen in this screenshot:

The boxes inside the cells indicate missing or superfluous cells.

Of course this method could be “exact” if we always choose the step size to be corresponding to the size of a single pixel on screen, meaning we would not be able to distinguish exact and inexact at this point, but this would imply a huge number of samples, which is most likely not efficient enough.

Line Rasterization Methods (e.g. DDA, Bresenham)

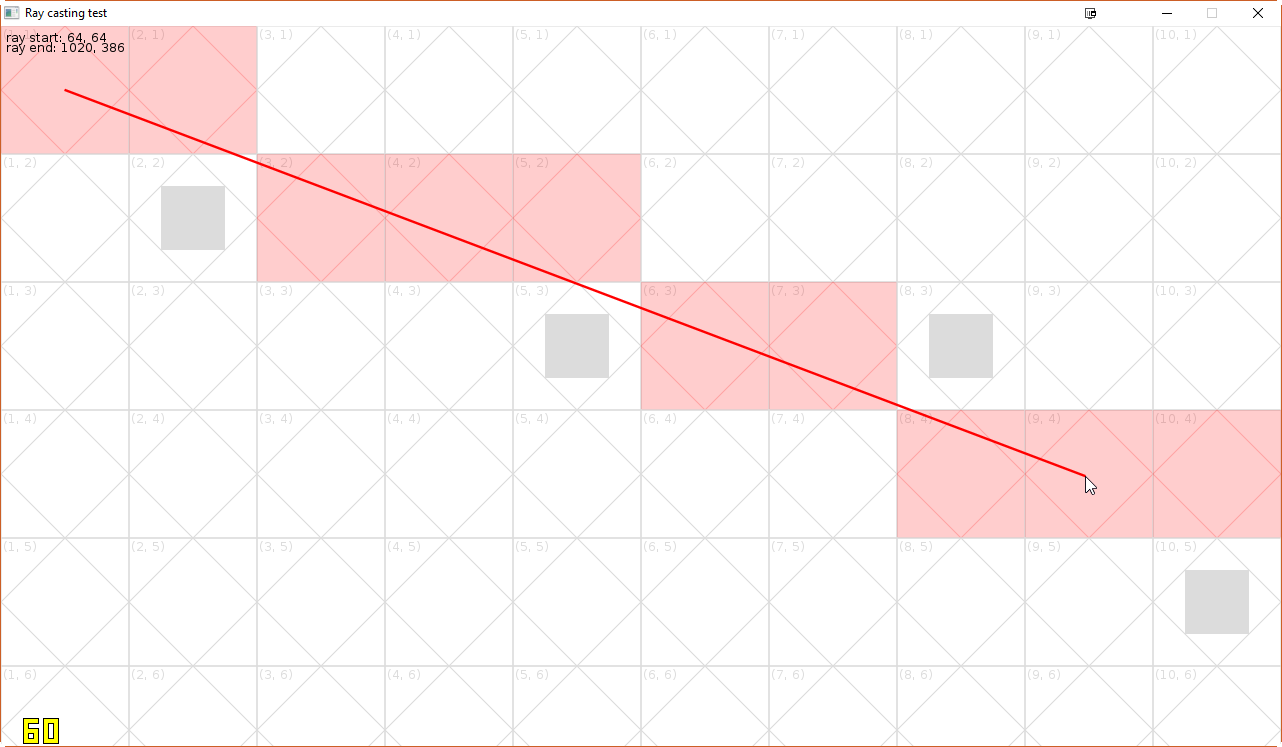

This might seem like the obvious choice and depending on your game (or the problem at hand) it might very well be, but in general this is also not sufficient, since these algorithms operate in (in our case) tile coordinates only, so that there will be no difference in a ray connecting the upper left corner of a tile and the lower right of another tile and a ray connecting the lower right corner of the same, first tile and the upper left corner of the other one. In fact most commonly line rasterization algorithms will rasterize every pixel, when a diamond shape in the pixel’s center intersects the line connecting the centers of the start and end pixel (the “diamond rule”). An example of this, including a visualization of the diamonds mentioned before, can be found in this screenshot (also from the example program, which has both DDA and Bresenham available):

Here you can see that we lose the information of where exactly inside the tile our start and end points are and also don’t treat the the tiles as axis aligned squares.

If you just need any line connecting your start and endpoint somehow, you might use a line rasterization method since they can be implemented very efficiently - and probably already have been, since they are so important for computer graphics in general. Also if your game has everything snapping to the tile grid and everything centered, this becomes an exact solution (a modern example would be Crypt of the Necrodancer)!

In my example program the functions implementing this are called castRay_DDA and castRay_Bresenham.

Exact Ray Casting

Simplified Case (direction positive)

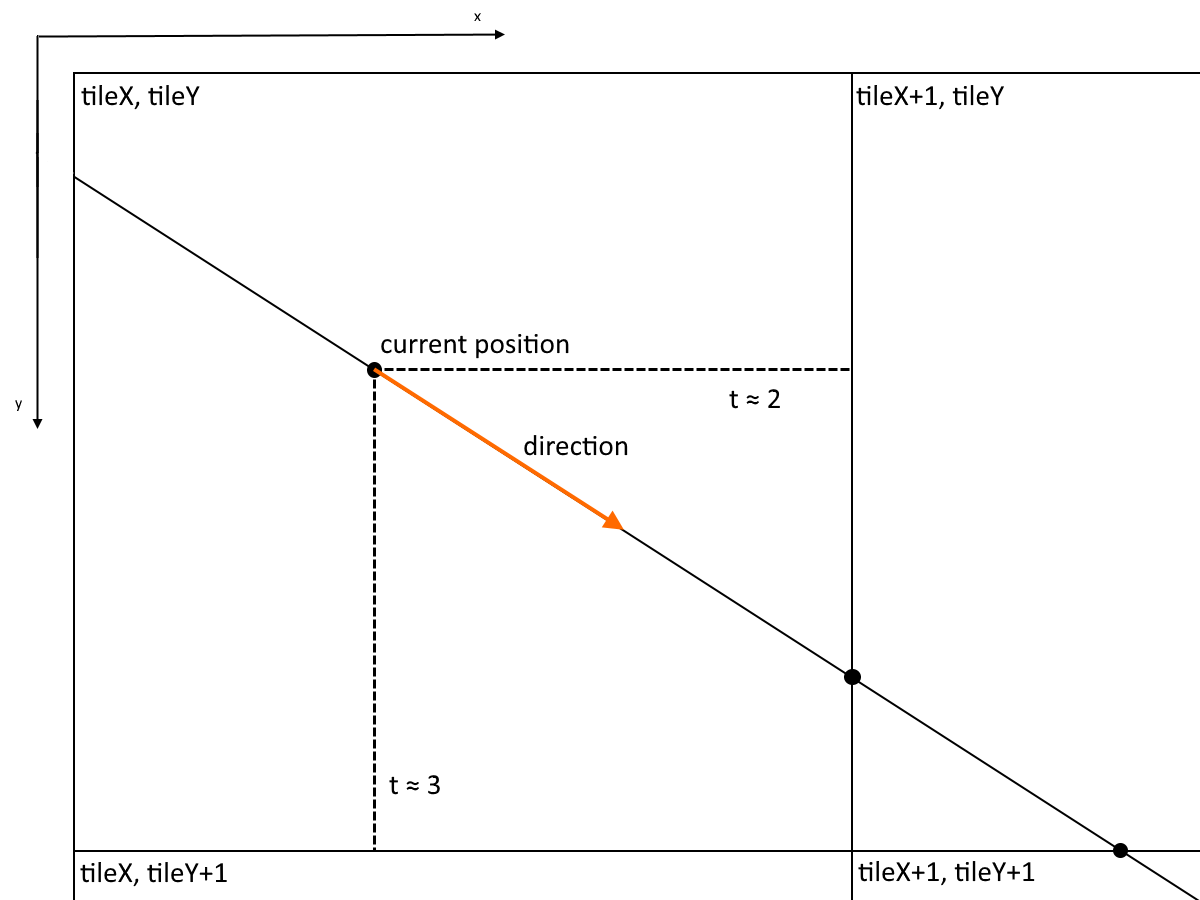

In a more (algorithmically) efficient method we would love to not visit cells twice, i.e. make no unnecessary steps and never miss anything. So if you want to find all intersections of the line with the grid and don’t miss any, at every step of the algorithm, you just have to find the first one, given your current position and direction.

If we consider the current position curX, curY, we can easily find the the tile coordinates of the tile curX, curY is in by dividing by the cell size and truncating the floating point part. Beware that, because we are using Lua for example code (since the example program is in Lua), arrays and tiles will be 1-indexed, i.e. start with index 1. So we will have to add 1 to both tile coordinates to get the final coordinate:

function tileCoords(cellSize, x, y)

return math.floor(x / cellSize) + 1, math.floor(y / cellSize) + 1

end

To get the next edges (assuming our direction is positive in x and y direction), we only have to add grid.cellSize, or in our cases, since we already added 1, do nothing but transform back to world coordinates, by multiplying with grid.cellSize. The distance to these edges can then be divided by the corresponding components of our direction vector to give us these distances in units of t!

local tileX, tileY = tileCoords(grid.cellSize, curX, curY)

local dtX = ((tileX)*grid.cellSize - curX) / ray.dirX

local dtY = ((tileY)*grid.cellSize - curY) / ray.dirY

To find the first intersection, we then only have to increment our current t by the smaller dt of the two and update our current position.

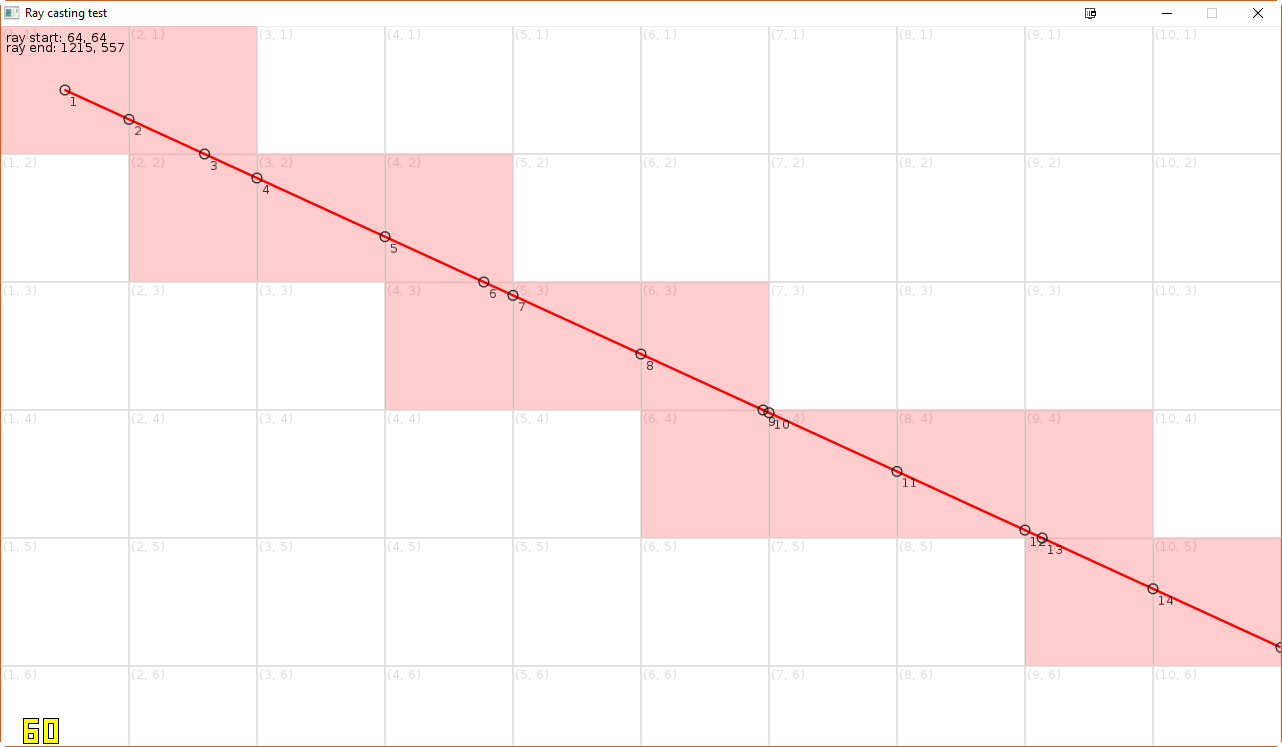

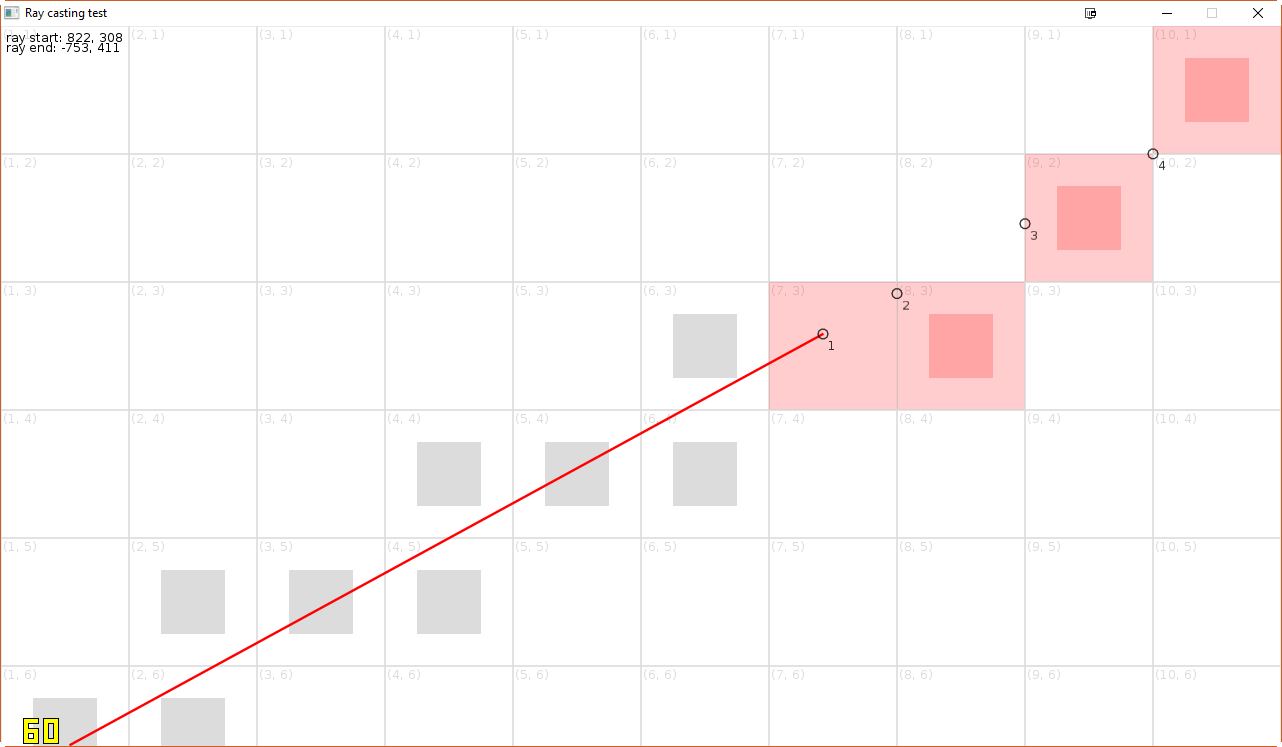

Implemented as the function castRay_clearer_positive, the results are exactly what we wanted!

Though, as mentioned before, negative directions (any axis) still give us some problems:

The reasons for this are obviously our flawed calculation for the next edge, since in the current case, we add 1 to the tile coordinates. In the negative cases, we would have to add zero, since the edges we want to hit are the ones of the current tile.

This is intentionally formulated to hint at the other problem, which is that if we jump to the next intersection, we will still be in the current tile and revisit the first intersection indefinitely! This is because math.floor maps values from [x, x+1) to x, so that a whole integer maps to itself, which is very sensible for a floor function, but is not entirely what we want.

Complete Case (all directions)

The problem of finding the next edge is trivial to solve, by introducing an offset of the tile coordinates that depends on the direction:

-- NOTE: 'cond and x or y' is a common idiom that is mostly equivalent to the

-- ternary operator i.e. equals x if cond evaluates to true and y otherwise

local dirSignX = ray.dirX > 0 and 0 or -1

local dirSignY = ray.dirY > 0 and 0 or -1

...

local dtX = ((tileX + dirSignX)*grid.cellSize - curX) / ray.dirX

local dtY = ((tileY + dirSignY)*grid.cellSize - curY) / ray.dirY

The floor-problem has multiple ways to solve it. One would be to rewrite our floor function so that it takes an additional parameter, which indicates which side of the interval should be open (i.e. not include the integer). Another one is to add an epsilon to our t, when incrementing it by either dtX or dtY, so that we will barely sneak into the next cell. Choosing this epsilon is a little tricky though since by introducing it, our algorithm will start to have edges it could overstep, just like the naive method. Any non-vanishing epsilon will have this as a result and even if we make it really small (of the order of a screen pixel size), we might run into issues when it just disappears because of floating point normalization, when ray casting in really big grids. This method might then resemble a naive method, with a really small step, which intelligently skips some samples, if possible.

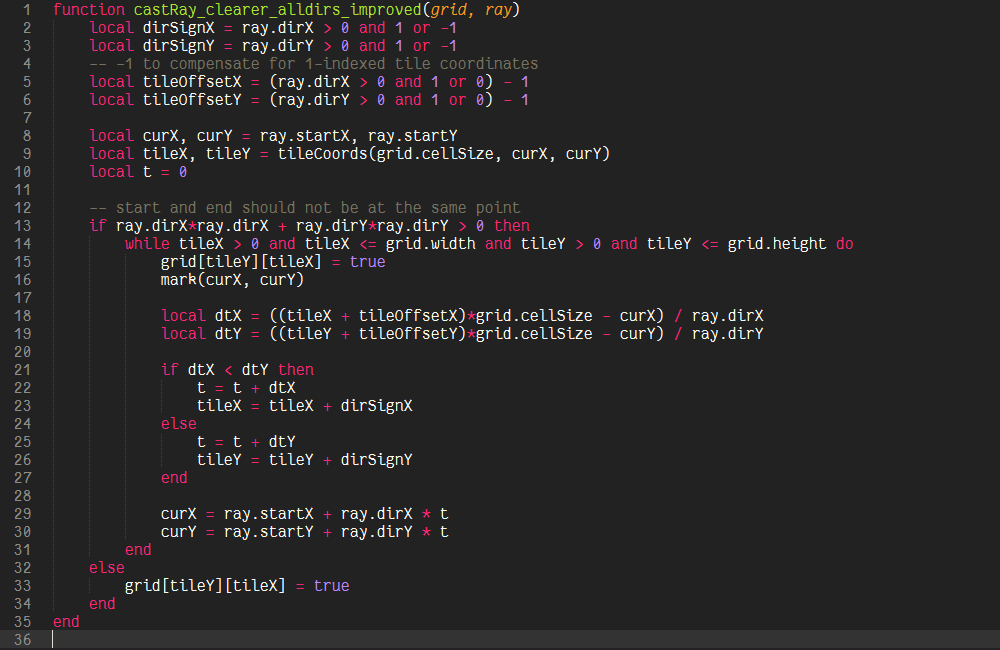

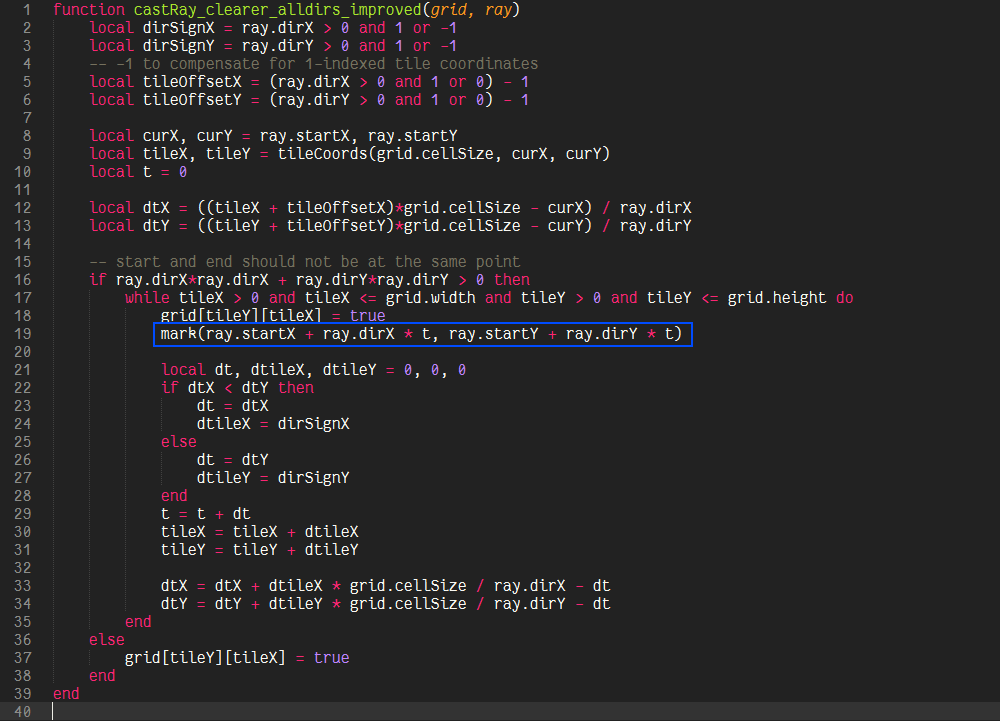

The best way though would probably be to introduce our own tile coordinates, which are not calculated from the current position, but kept track of alongside it. Then we can just decide to increment/decrement these at the right times - tileX when dtX < dtY and tileY otherwise. This is implemented in the function castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved.

Final Solution

The hawkeye programmer might have noticed that our castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved is a little more complicated than it should be. You have to watch a little more closely but some terms in the calculation of dtX and dtY might be constant and maybe we can eliminate the division. In fact we can and with a little more transforms and noticing that all our constants are symmetric in x and y, so that we might as well write a helper function that calculates these independent of axis, we arrive at our new function castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved_transformed (thank god this article is going to end soon, these names are getting long). The necessary transformations to arrive at this function are shown in the following images:

The unmodified version of castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved:

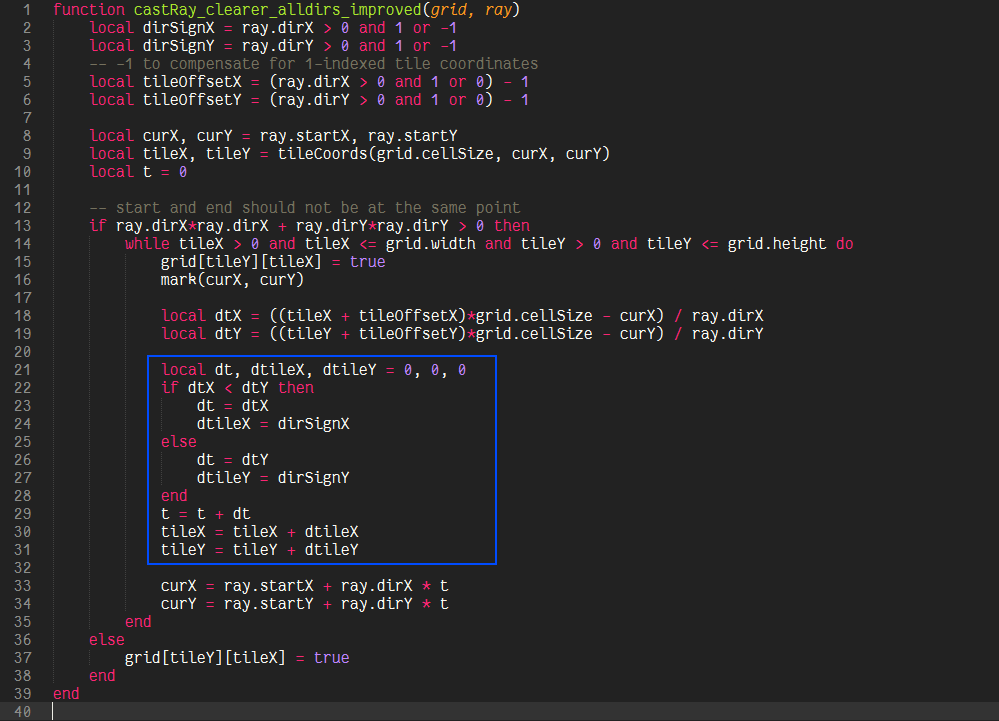

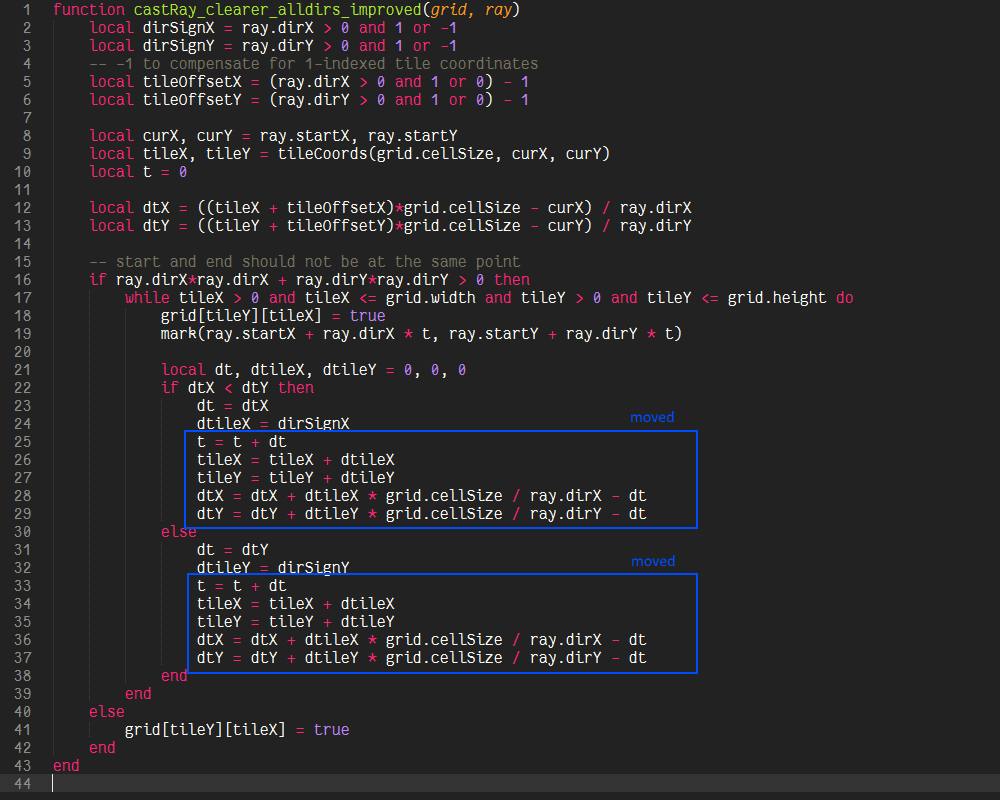

The part with the central logic is replaced so the actual modification of the central variables happens outside. This is so we can identify the delta of dtX and dtY more easily:

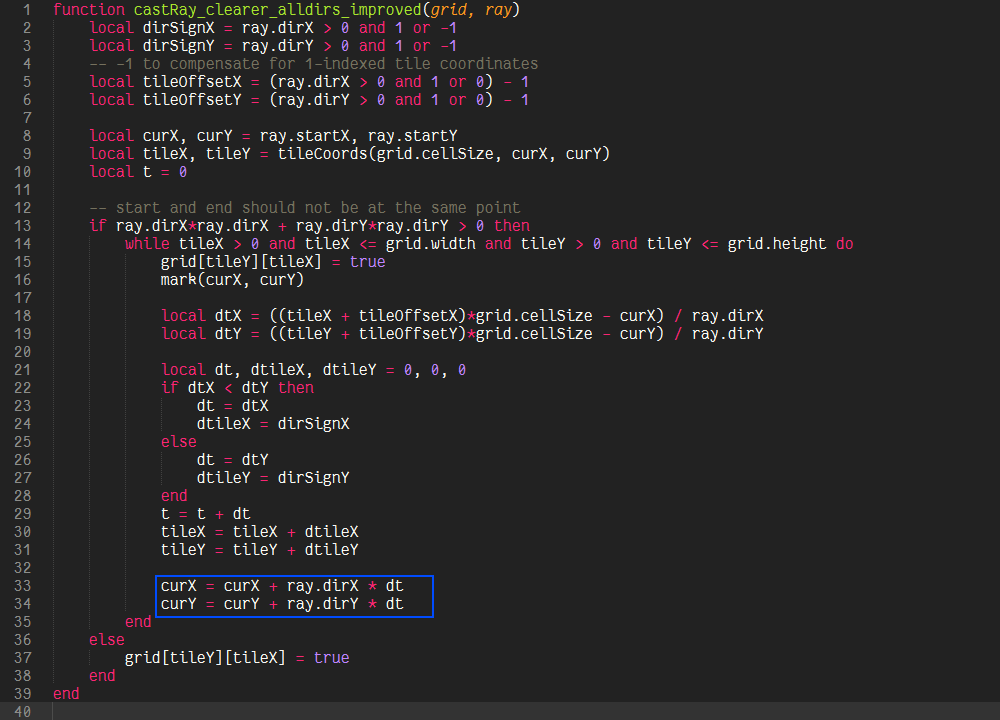

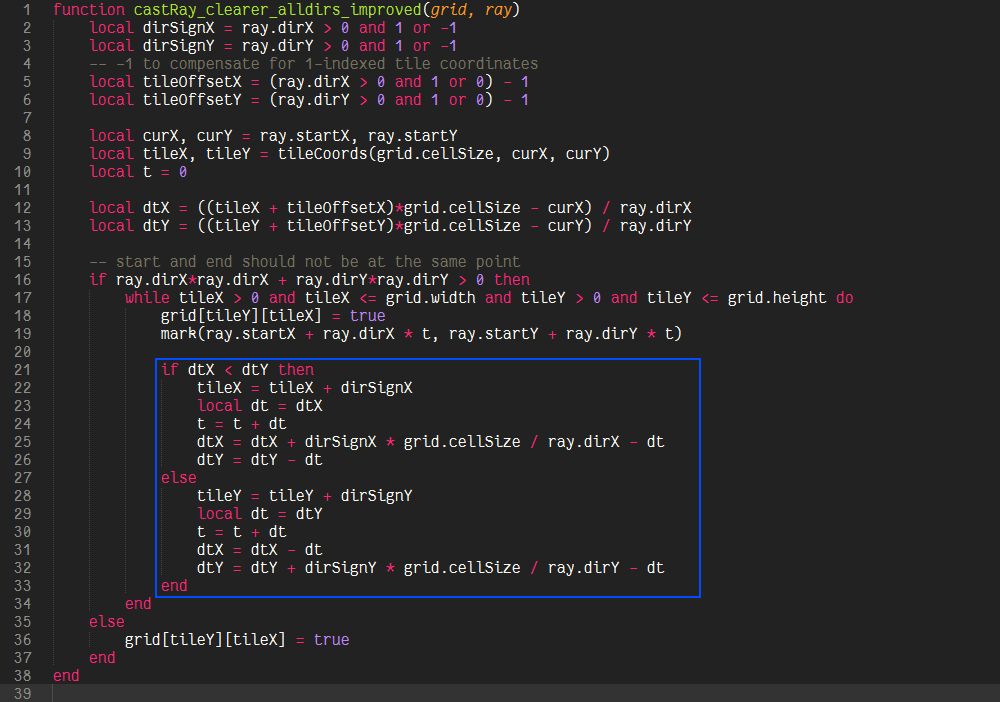

Again we simplify to ease the identification of the delta of dtX and dtY by wirting the change in curX and curY with dt instead of t:

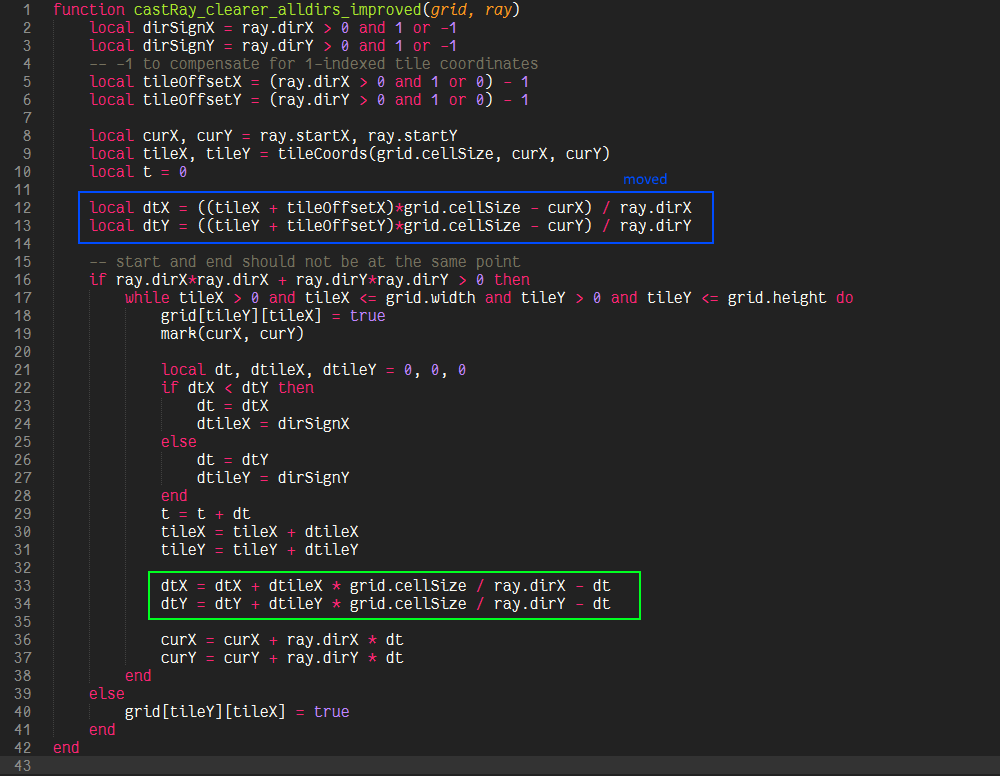

Here we “pull out” the first assignment of dtX and dtY and only apply deltas in the main loop of the algorithm, which can be identified by subtracting the dtX and dtY of two successive iterations:

At this point we don’t need curX and curY anymore and can just put it into our mark-function, which is only used for visualization:

To simplify further, we prepare by putting all assignments after the if into the cases, so that we can optimize them separately and for their special cases):

We just plug in the known values of dtileX and dtileY and reorder a little:

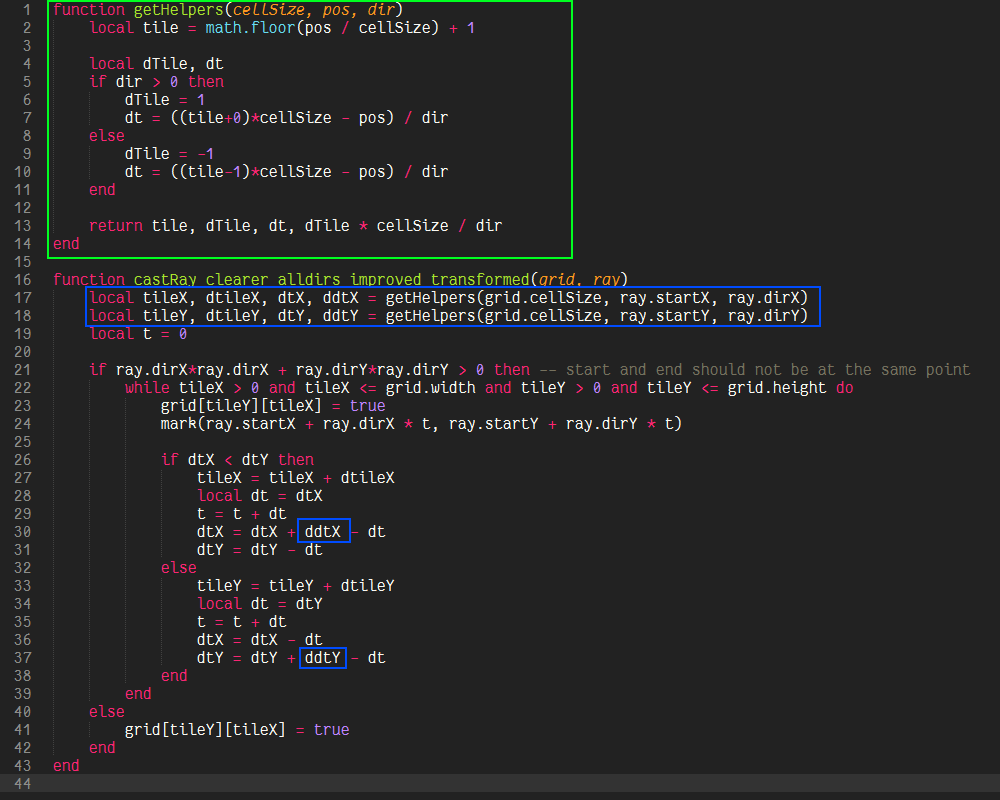

Now we use that all intermediate variables defined at the top are symmetric in x and y and can be calculated by a common function. We also take out the division from the main loop, since the summand is constant through all iterations (ddtX and ddtY) and rename dirSignX/dirSignY to dtileX and dtileY:

One branch and 5 additions per step and a setup function (a little trickier though, but constant time) is probably as good as it can get, though it is definitely not as apparent what is actually happening in this function. If we decide that we have no use for t and therefore the intersection points themselves (and just want to visit some cells, or want to know if there is a possible path at all), then we can eliminate t all together and because we don’t care about the actual values of dtX and dtY, we can decide to omit the “- dt” term, because the comparison in the next iteration will still yield the same result, so that our algorithm would be reduced to one branch and two additions. This is in fact the algorithm described in “A Fast Voxel Traversal Algorithm for Ray Tracing” by John Amanatides and Andrew Woo, which inspired the transformations done to castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved.

All in all, I showed you what the problems of ray casting in 2D grids are and what kind of solutions for them exists or seem to exist, but turn out to be a fluke. And also made a nice connection to another algorithm, which many use without understanding it properly, by deriving it from an easier to understand one and applying some transformations.

Comments (from old blog)

Dave (2016-11-22 20:55:08)

Thanks for this - it’s one of the more straightforward explanations for this topic I’ve found. If you start at 64,64 and your direction is 1,1, the ray ends up passing through the corners. Because of this code:

if (dtX =. This ends up always selecting the lower left grid cell and you end up with a stair step pattern. I’ve not found any way to deal with that in a more consistent way. I’d like to either select both potential matches (the lower left and upper right cell if that makes sense) or neither of them. The former would be best. Any idea how to do that?Dave (2016-11-22 21:15:30)

Looks like the code was removed because of the tags. If you look in the final screen shot it’s the code in lines 26 and 32 where it’s comparing dtx and dty.

Joel (2016-11-22 21:25:12)

Hey Dave, I’m really happy a real person actually found and read this. I’m already happy about writing this! Thanks a lot!

I’m not sure what “if(dtX = ” is referencing. I cannot find an equal-comparison for dtX in my code, but I wrote it a good while ago, so I might be missing something obvious. I noticed that some functions exhibit the behaviour you were describing and others not. Specifically castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved and castRay_clearer_alldirs_improved_transformed do have the stairstep-pattern, while castRay_accurate, castRay_clearer_positive and castRay_clearer_alldirs do not!

You can try comparing them and see how I seemingly broke it in the “improved” versions. If you want/can wait I will find it out myself on Thursday or Friday, when I finished an assignment I’m currently working on.

Joel

Reedik (2019-04-26 10:30:26)

There is also a case where either X or Y direction is 0. So the getHelpers method should include

Martin Haye (2020-08-02 23:07:31)

Thank you for this. This is the clearest explanation of 2d grid traversal I’ve found, and I’m impressed by how you started at first principles and worked your way through to an efficient, accurate algorithm. But the best part for me is that I needed an algorithm that keeps track of ‘t’ because I need the distance at the end. It’s rare to find that. This is perfect.

Dark (2021-06-16 20:16:00)

if dtX and dtY is equal (aka the angle of the ray is 45 degreees)it will just choose dtX instead, but it should just have another check to see if they are equal or not and if they are just increment both x and y